Inclusivity in Cellular and Molecular Biology

Oliver Malatich

10/11/2022

BIOL 302

Dr. Stephanie Ackerson

Women, people of color, and LGBT+ individuals are often looked over in textbooks and classrooms. Here are three biologists from underrepresented communities and the important discoveries they have made.

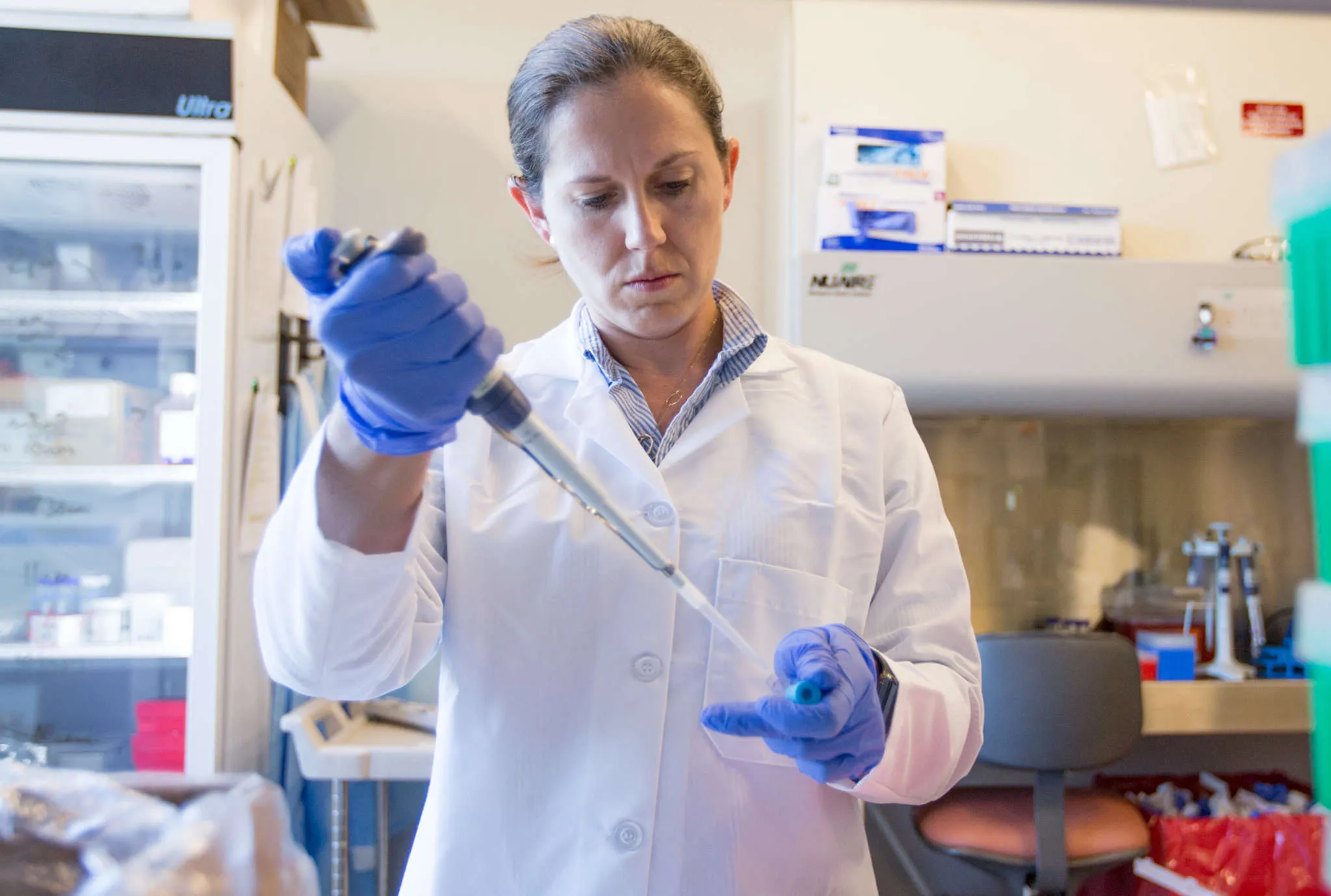

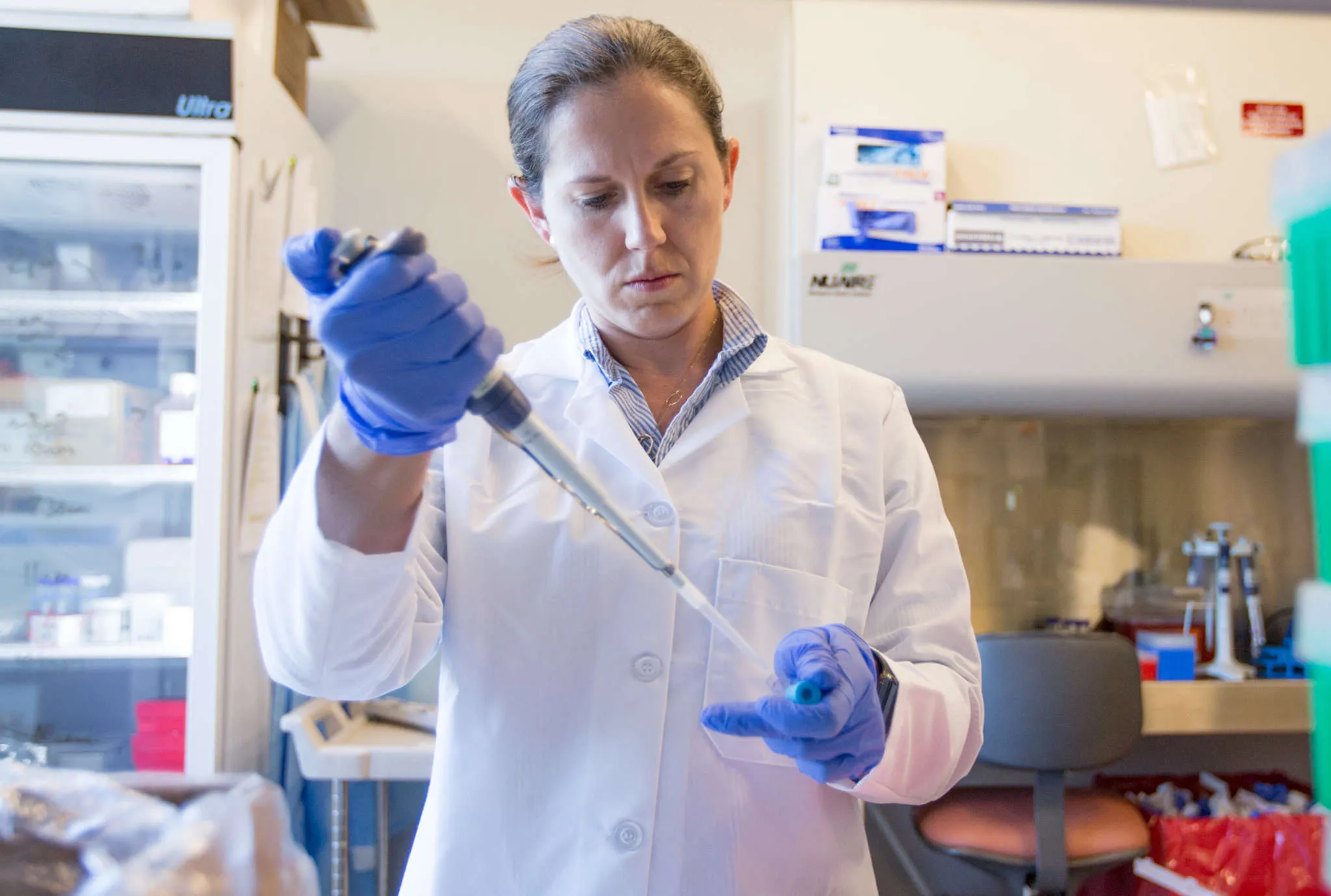

Maggie Wesberry Schmierer

Maggie Schmierer was born and raised in Baton Rouge and is now a laboratory manager and technician who currently manages scientific operations at Carisma Therapeutics.

She developed many of the skills needed for scientific research from baking. Her experience following recipes and adding the precise amount of each ingredient gave her a leg up when she performed chemistry experiments. Observing the characteristics of a failed dish and comparing it to the errors made in following the recipe could lay a foundation for the scientific method and spark curiosity about the chemical properties of each ingredient. This provided her with a different background from many of her male peers who were likely discouraged from baking when they were young.

Her interest in science was little more than an interest until one career day in elementary school when a parent came in to discuss his chemical patents. This gave her an understanding of how science could become a career. Because of this parent, she felt like it was possible to make a living doing scientific research.

She received her bachelor's degree in biology from Louisiana State University with a minor in chemistry and went on to get her master’s degree in biotechnology from Johns Hopkins University. She started as a research assistant at the Henry M Jackson Foundation and worked her way up to laboratory manager while researching HIV and vaccines. There, she studied the role of natural killer lymphocytes in the assessment of HIV-1 neutralization. She published her first paper on this topic in 2012.

She moved on to develop vesicle flow cytometry assays as director of lab operations at CytoVas, and then to Carisma Therapeutics to manage assay development. There, she studied potential applications of CAR T-cells in treating solid tumors as opposed to hematological cancers. She found that CAR macrophages were able to promote inflammation in solid tumors and prolong survival.

Maggie Schmierer made great advances in the treatment of two of the most notorious diseases in the world. She is currently researching the role of monocyte and macrophage-derived extracellular vesicles in predicting post-operative heart attacks, as well as the production of exosomes by rejected donor lungs. Her research will provide insight to the potential medical value of exosomes and extracellular vesicles. Her work may help keep patients from rejecting their transplanted organs.

Maggie continues to be a fantastic baker and a wonderful role model for her nieces and nephews.

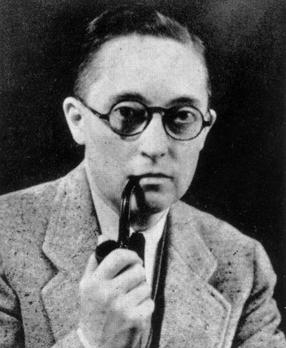

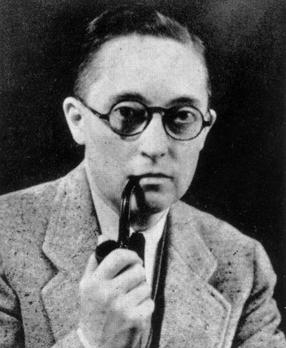

Alan Hart

Alan Hart was a tuberculosis researcher who lived from 1890 to 1962. He was also a novelist, and one of the first American transgender men to have a hysterectomy in 1917.

Alan Hart was born in Kansas, and moved to Albany, Oregon at the age of 12. He was incredibly self-reliant. He liked to play doctor, and even once dressed his own wound after chopping off his fingertip with an axe. He graduated from Albany College in 1912 and went on to get his medical degree from the University of Oregon in 1917. Unfortunately, his medical degree was under his birth name, and he was only able to work at a hospital if he chose to present as female.

He eventually started a medical practice, but when a classmate from medical school recognized him, he had to move and change jobs over and over to avoid being outed. In the 30s and 40s, he wrote four novels about social injustices in the medical field. He was well aware of stigma, and it’s likely that this allowed him to work with tuberculosis patients at a time when a TB diagnosis was a mark of shame. He called his clinics “chest clinics” so his patients could get discreet care without feeling judged.

Hart studied tuberculosis at a time when it was the deadliest disease in the country. Scientists at the time had determined that it could hypothetically be cured if it was detected soon enough, but tuberculosis typically had no symptoms until it became untreatable. Scientists at the time knew that tuberculosis started in the lungs, but Hart was the one to discover that it spread through the circulatory system.

X-rays were only discovered in 1895 and were used to detect broken bones and tumors, but Hart applied this new technology to the lungs. He used X-ray screening to detect tuberculosis before it became symptomatic. Working to end the stigma of a tuberculosis diagnosis, he started a campaign to encourage nationwide X-ray screening so that affected individuals could be isolated for their recovery.

When little is known about a deadly disease, a social stigma is attached to those affected. This is a social adaptation that works to decrease the number of people interacting with infectious individuals. However, this stigma also applies to the medical field, and makes it more difficult for doctors and researchers to learn enough about the disease to treat it properly. However, Hart dealt with similar stigma his whole career, and was not fazed by this. His unique background gave him a psychological advantage that other researchers didn’t have. It is likely that, had he been alive during the AIDS crisis of the 80’s, he would’ve given HIV patients the same compassion and understanding that he gave to TB patients.

Shortly before he died of heart failure in 1962, he gave a speech to graduating medical students in which he said,

“Each of us must take into account the raw material which heredity dealt us at birth and the opportunities we have had along the way, and then work out for ourselves a sensible evaluation of our personalities and accomplishments.”

Ben Barres

Ben Barres was born in 1954 in New Jersey. He had a great interest in science and mathematics that he developed at West Orange Public Library. He received his bachelor’s degree in life science from Massachusetts Institute of Technology and his MD from Dartmouth in 1979. He wrote about sexism and vouched for women in the scientific community.

Where Alan Hart was required to hide, Barres was openly transgender, and did so to provide his unique insight on the sexism he experienced before his transition. Cis men have their own experience and can’t fully understand the plights of a woman in STEM. Barres was in a unique situation where he was able to see both sides of the story and used that to advocate for equality in the sciences with his essay, 'Does gender matter?'. There were many instances of sexism he experienced before his transition that he didn’t even recognize until he transitioned in 1997.

During his residency at Cornell, he noticed that the causes of neurodegeneration weren’t well studied, and when he noticed unusual patterns of glial cells near degenerating regions, he decided to leave his residency to study neuroscience at Harvard Medical School so he could research glial cells and answer his own question.

He studied the most common cell in the human brain: astrocytes. The function of these glial cells was unknown, but Barres discovered their role in synapse formation and activation, as well as their role in assisting microglia with synaptic pruning.

Barres wondered why many neurons in the developing vertebrate nervous system became apoptotic shortly after forming connections. He determined it was because the dying cell didn’t receive enough neurotrophic factors from the target cell. These factors are present in many cells in the body and suppress the newly formed cell’s default plan of apoptosis.

It’s clear that Ben Barres did what he wanted and knew what was best for him and for his goals as well as the scientists around him. he shared his research techniques istead of keeping them secret. He was dedicated and often worked in the lab until late at night, even sleeping there. He followed his passions, and it led him to important discoveries. He learned from his experiences, educated the public, and made a difference in both his field and his community. He died of pancreatic cancer in 2017.

Reflections

It’s unfortunate that so many skilled women and transgender individuals have their work overlooked for the simple reason that publications are sorted by name. Alan Hart had this problem with his medical degree, and much of Ben Barres’ research is still under his birth name. The practice of a married woman adopting her husband’s last name can also make it more difficult for her research to be accessed. Perhaps this could be solved in the future by assigning scientists an identification number. Transgender individuals could be allowed to release work under their chosen name, or papers could be republished. A solution will likely be found in the near future as copyright laws begin to change to suit the digital age.

I started as a music student, and eventually became interested in neuroscience and insects. Playing around with my lazy eye as a child led me to an interest in stereography. I had positive role models in my family members and teachers, and I find joy in understanding the world around me and finding creative solutions to problems. I thought of working in conservation, but protein design seems like an interesting and active field with potential for new 3-D imaging technology. I believe that conserving the genetic diversity of species around the world will give us solutions to the many problems facing our species and our planet, including ones that our own inventions have caused. No solution comes without problems of its own, but by studying what we know, we can apply these concepts to better understand the results of our actions. Science is a field where daring leaps are made regularly, but the important part is that these new advances are approached cautiously and methodically.

The sciences are predominately dominated by white males. This leads research to be primarily focused on the interests of white males, leading to conclusions drawn from the logic of people with similar backgrounds. Groups with more diversity come up with more creative solutions to problems and are more likely to explore a greater range of ideas.

The field of biology can change gradually with each new generation. As we continue to provide opportunities and scholarships to women and people of color in STEM, the field can gradually change to become a better representation of the population of Earth. Science is for everybody, and its results can benefit different groups in different ways. Showing the negative impact that discrimination has on research allows society as a whole to change in a way that leaves our system of social hierarchies behind so that the human race can collaborate for the good of all.